Phaistos

Phaistos

The

Palace of Phaistos lies on the East end of Kastri hill at the

end of the Mesara plain in Central Southern Crete. To the

north lies Psiloritis, the highest mountain in Crete. On the

slopes of Psiloritis is the Kamares cave, probably a religious

or cult centre for Phaistos and the Mesara plain. In this cave

a very fine pottery style was discovered from the Middle

Minoan period, which has been named Kamares Ware after the

cave in which it was found.

Kamares

ware has only been found at Palace sites like Phaistos and

Knossos, suggesting that it was specially produced for

whatever elite was based in the Palaces. To the south of

Phaistos are the Asterousia mountains beyond which lies the

Libyan Sea. To the south west is Kommos, the ancient port of

Phaistos and to the east, the vast Mesara plain. Kamares

ware has only been found at Palace sites like Phaistos and

Knossos, suggesting that it was specially produced for

whatever elite was based in the Palaces. To the south of

Phaistos are the Asterousia mountains beyond which lies the

Libyan Sea. To the south west is Kommos, the ancient port of

Phaistos and to the east, the vast Mesara plain.

The

Palace was excavated by the Italian archaeologist Halbherr at

the beginning of the 20th century. The earliest settlements on

the site, which lies close to the Yeropotamos, one of the few

rivers in Crete to flow all year round, dates from the

Neolothic Period (c. 4000 BC) . It is likely that in the Early

Minoan period small settlements were scattered over the hill

on which the Palace later stood. Dark on light pottery (Agios

Onouphrios ware) has been found in the prepalatial levels on

the hill, but no Vasiliki ware from the Early Minoan II period

has been found on the site. The

Palace was excavated by the Italian archaeologist Halbherr at

the beginning of the 20th century. The earliest settlements on

the site, which lies close to the Yeropotamos, one of the few

rivers in Crete to flow all year round, dates from the

Neolothic Period (c. 4000 BC) . It is likely that in the Early

Minoan period small settlements were scattered over the hill

on which the Palace later stood. Dark on light pottery (Agios

Onouphrios ware) has been found in the prepalatial levels on

the hill, but no Vasiliki ware from the Early Minoan II period

has been found on the site.

The

Old Palace was built on the site at the beginning of the

Second Millenium, known as the Protopalatial Period (c.

1900-1700). Twice it was severely damaged by earthquakes and

rebuilt so three distinct phases are visible to

archaeologists. Levi, who excavated here from 1950 to 1971

believed that the first two phases of the Old Palace of

Phaistos constitute the oldest Palatial buildings in Crete.

Other finds at the site include thousands of seal impressions

and some tablets containing the Linear A script from Middle

Minoan II. Linear A has also defied all attempts so far to

decipher it. The

Old Palace was built on the site at the beginning of the

Second Millenium, known as the Protopalatial Period (c.

1900-1700). Twice it was severely damaged by earthquakes and

rebuilt so three distinct phases are visible to

archaeologists. Levi, who excavated here from 1950 to 1971

believed that the first two phases of the Old Palace of

Phaistos constitute the oldest Palatial buildings in Crete.

Other finds at the site include thousands of seal impressions

and some tablets containing the Linear A script from Middle

Minoan II. Linear A has also defied all attempts so far to

decipher it.

When

the Old Palace was finally destroyed a new palace was built on

the site. Fortunately for us, the builders of the new palace

did not destroy all traces of the old. In fact much of the old

palace was covered over at the time of the building of the new

palace in order to level the ground. Some of the old palace

can still be seen by visitors but much of it is accessible

only to the experts. When

the Old Palace was finally destroyed a new palace was built on

the site. Fortunately for us, the builders of the new palace

did not destroy all traces of the old. In fact much of the old

palace was covered over at the time of the building of the new

palace in order to level the ground. Some of the old palace

can still be seen by visitors but much of it is accessible

only to the experts.

The New

Palace covers a smaller area than the old, thus enabling the

visitor to see some of the remains of the Old Palace,

including the area where the Phaistos Disc was discovered.

However, excavators have been surprised by the lack of finds

that one would expect at a Minoan Palace. No frescoes have

been found in the New Palace and there is a complete absence

of sealings and tablets. One view suggests that in the New

Palace period the importance of Phaistos decreased while that

of Agia Triada nearby continued to grow and that the two

settlements complemented eachother in some way. The New

Palace covers a smaller area than the old, thus enabling the

visitor to see some of the remains of the Old Palace,

including the area where the Phaistos Disc was discovered.

However, excavators have been surprised by the lack of finds

that one would expect at a Minoan Palace. No frescoes have

been found in the New Palace and there is a complete absence

of sealings and tablets. One view suggests that in the New

Palace period the importance of Phaistos decreased while that

of Agia Triada nearby continued to grow and that the two

settlements complemented eachother in some way.

The site is

entered at the level of the Upper West Court, which was used

by both the old and the new palace. The Upper West Court is

joined to the Lower West Court by a staircase which was built

a the time of the upper court and was in use at the time of

the old palace. To the north of the court is a very high wall

and in front of this wall is the theatral area, with two

raised walkways. There are eight rows where spectators either

sat or stood to watch religious rites, ceremonies or whatever

else took place there. The site is

entered at the level of the Upper West Court, which was used

by both the old and the new palace. The Upper West Court is

joined to the Lower West Court by a staircase which was built

a the time of the upper court and was in use at the time of

the old palace. To the north of the court is a very high wall

and in front of this wall is the theatral area, with two

raised walkways. There are eight rows where spectators either

sat or stood to watch religious rites, ceremonies or whatever

else took place there.

The main

entrance to the New Palace was from the West Court, up the

dozen steps of the 14 metre wide Magnificent Staircase, at the

top of which is an equally wide landing, behind which stood

the Monumental Propylaia. This structure is the forerunner of

the Propylaia of Classical Greek times. The main

entrance to the New Palace was from the West Court, up the

dozen steps of the 14 metre wide Magnificent Staircase, at the

top of which is an equally wide landing, behind which stood

the Monumental Propylaia. This structure is the forerunner of

the Propylaia of Classical Greek times.

Between the

landing and the actual entrance itself, were two porticos.

Hutchinson points out that if the West entrance to palaces was

direct, then it was small, but if it was indirect then it was

grand. Here, the main entrance does not lead directly into the

Central Court and is very grand. Between the

landing and the actual entrance itself, were two porticos.

Hutchinson points out that if the West entrance to palaces was

direct, then it was small, but if it was indirect then it was

grand. Here, the main entrance does not lead directly into the

Central Court and is very grand.

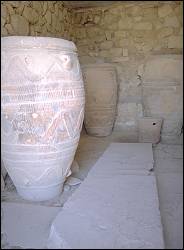

To the south

of the Propylaia is to be found the Palace magazine or storage

area. This consisted of ten rooms, five on each side, opening

onto an east-west corridor, which at its east end opened out

into a two-columned hall with a portico facing the Central

Court. One storage room remains in tact with a number of

pithoi inside (see photo above). To the south

of the Propylaia is to be found the Palace magazine or storage

area. This consisted of ten rooms, five on each side, opening

onto an east-west corridor, which at its east end opened out

into a two-columned hall with a portico facing the Central

Court. One storage room remains in tact with a number of

pithoi inside (see photo above).

The Central

Court lies to the east of the magazines. It measured 55 metres

by 25 metres. The South East part of the Central Court is now

missing. Given the large number of corridors which lead to the

Central Court, it must have been central to the life of the

Palace itself. It was lined on two sides by porticos with

alternating columns and pillars. The Central

Court lies to the east of the magazines. It measured 55 metres

by 25 metres. The South East part of the Central Court is now

missing. Given the large number of corridors which lead to the

Central Court, it must have been central to the life of the

Palace itself. It was lined on two sides by porticos with

alternating columns and pillars.

The

north-east wing of the palace is considered to have consisted

of artisans' workshops and the remains of a furnace for

smelting metal can still be seen in the courtyard. The

south-east wing collapsed some time in the past and the hill

has eroded to beyond the point where the it would have stood. The

north-east wing of the palace is considered to have consisted

of artisans' workshops and the remains of a furnace for

smelting metal can still be seen in the courtyard. The

south-east wing collapsed some time in the past and the hill

has eroded to beyond the point where the it would have stood.

Much of the

West wing of the central court, south of the magazines, was

used for religious purposes. It contained a number of rooms

which opened directly onto the Central Court. Just south of

the corridor of the magazines, in the West Wing, there are two

rooms with benches lining the walls. Thes benches were covered

with gypsum, a material used extensively at Phaistos. Further

south there is a pillar crypt similar to those found at other

Palaces and also in the remains of the old palace at Phasitos,

but this one is on a rather more modest scale than, for

example, the one at Malia. Much of the

West wing of the central court, south of the magazines, was

used for religious purposes. It contained a number of rooms

which opened directly onto the Central Court. Just south of

the corridor of the magazines, in the West Wing, there are two

rooms with benches lining the walls. Thes benches were covered

with gypsum, a material used extensively at Phaistos. Further

south there is a pillar crypt similar to those found at other

Palaces and also in the remains of the old palace at Phasitos,

but this one is on a rather more modest scale than, for

example, the one at Malia.

The area

also contained two lustral basins. Cult vases and figurines

were found in this part of the West Wing, and the shapes of

double axes were incised on the stone, all adding to evidence

of a religious use for the building. The area

also contained two lustral basins. Cult vases and figurines

were found in this part of the West Wing, and the shapes of

double axes were incised on the stone, all adding to evidence

of a religious use for the building.

The

conventional view is that whereas the West Wing of the palaces

were used for religious and administrative purposes, the East

Wing contained the domestic apartments of the royal family.

However, a lustral basin was originally situated in the East

Wing and if the purpose of the lustral basin was religious

rather than hygenic, that would tell against the theory that

the East Wing comprised domestic quarters. The

conventional view is that whereas the West Wing of the palaces

were used for religious and administrative purposes, the East

Wing contained the domestic apartments of the royal family.

However, a lustral basin was originally situated in the East

Wing and if the purpose of the lustral basin was religious

rather than hygenic, that would tell against the theory that

the East Wing comprised domestic quarters.

The

so-called Royal Apartments are in the north part of the

Palace, to the East of the Monumental Propylaia. The smaller

"Queen's Megaron" lies to the south of the larger

"King's Megaraon". These rooms would have had light

wells, porticoes and pier-and-door partitions which would have

enabled sections of the room to be closed off. The lower walls

and floors were lined with slabs of alabaster. To the west of

the King's room is possibly the best-preserved Lustral Basin

in Crete. The

so-called Royal Apartments are in the north part of the

Palace, to the East of the Monumental Propylaia. The smaller

"Queen's Megaron" lies to the south of the larger

"King's Megaraon". These rooms would have had light

wells, porticoes and pier-and-door partitions which would have

enabled sections of the room to be closed off. The lower walls

and floors were lined with slabs of alabaster. To the west of

the King's room is possibly the best-preserved Lustral Basin

in Crete.

On the

slopes of the hill to the south of Phaistos and on level

ground below the hill stood the Minoan town. This is still

being excavated though part of it can be seen below from the

perimeter of the Palace site. On the

slopes of the hill to the south of Phaistos and on level

ground below the hill stood the Minoan town. This is still

being excavated though part of it can be seen below from the

perimeter of the Palace site.

There are

many reasons why a visitor to Crete should make the effort to

visit Phaistos. It has the most beautiful setting of any of

the Minoan Palaces, it does not get quite so crowded as

Knossos and even in the summer it is possible to have the site

almost to oneself provided one arrives at opening time or

alternatively an hour or two before closing time. Finally, it

is a much more intimate site than Knossos where walkways of

scaffolding scar the Palace and so much of Knossos has been

roped off, preventing access to visitors, who must look from a

distance. There are

many reasons why a visitor to Crete should make the effort to

visit Phaistos. It has the most beautiful setting of any of

the Minoan Palaces, it does not get quite so crowded as

Knossos and even in the summer it is possible to have the site

almost to oneself provided one arrives at opening time or

alternatively an hour or two before closing time. Finally, it

is a much more intimate site than Knossos where walkways of

scaffolding scar the Palace and so much of Knossos has been

roped off, preventing access to visitors, who must look from a

distance.

No doubt these

measures were necessary to protect the Palace of

Knossos from the hundreds of thousands of tourists

who swarm all over the site from April to October

each year. Similar measures may one day be necessary

at Phaistos. Until then, an early morning or early

evening visit will allow you to wander round the

site in a way that simply isn't possible at Knossos

and to break off from looking at the ruins to view

some of the most spectacular scenery that Crete has

to offer.

No doubt these

measures were necessary to protect the Palace of

Knossos from the hundreds of thousands of tourists

who swarm all over the site from April to October

each year. Similar measures may one day be necessary

at Phaistos. Until then, an early morning or early

evening visit will allow you to wander round the

site in a way that simply isn't possible at Knossos

and to break off from looking at the ruins to view

some of the most spectacular scenery that Crete has

to offer.

|